Public Health Concern: How Pandemic Covid-19 Affect Public Health

The new coronavirus has affected people’s health in more ways than one. We will look at what the pandemic has meant for public healthcare and primary healthcare access in countries around the world. The World Health Organization (WHO) define primary healthcare as “a whole-of-society approach to health and well-being centered on the needs and preferences of individuals, families, and communities.”

WHO explains that primary healthcare ensures people receive comprehensive care, ranging from promotion and prevention to treatment, rehabilitation, and palliative care — as close as feasible to people’s everyday environment. Access to healthcare is a fundamental human right, but the strain that the COVID-19 pandemic has placed on healthcare systems everywhere has, in turn, affected many people’s primary care provision.

Impact on expectant parent

The spread of the virus makes people around the world covered in fear, makes the healthcare providers around the world have been minimizing in-person contact with their patients. This has affected prenatal care, a crucial aspect of ensuring that pregnant women and developing babies stay healthy throughout pregnancy. The Office on Women’s Health at the Department of Health & Human Services advise frequent checkups and screenings for pregnant women. They note that these should include one checkup per month during weeks 4–28 of the pregnancy, two per month during weeks 28–36, and weekly checkups from then on until the birth. However, the pandemic has jeopardized these regular prenatal visits to the obstetrician or even made them impossible. So most of the appointments have turned to telemedicine completely. Specialists argue that telemedicine is more convenient and safe, allowing pregnant women to receive the support they need without placing themselves at risk by attending clinic appointments in person during the pandemic.

Missed vaccines could lead to other outbreaks

While healthcare organizations such as the CDC continue to stress the importance of immunizing children against other viruses, they also note that the number of children receiving their vaccines has dropped significantly of late. This could, in part, result from lock down measures and stay-at-home policies, but it is also likely to be due to the aforementioned cancellations of and delays in primary care appointments.

“Millions of children missing out on routine vaccines is an alarm bell and risks further outbreaks of life threatening diseases like measles.”– Sacha Deshmukh, UNICEF U.K. According to a briefing from the WHO Director-General, Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, a recent WHO report suggests that “the rate of progress (in healthcare worldwide) is too slow to meet the Sustainable Development Goals and will be further thrown off track by COVID-19.”

The Sustainable Development Goals are an extensive agenda that the United Nations (UN) have adopted with the aim of curbing poverty and other deprivations, including in the realm of healthcare globally by 2030.

Effect to Public Health

The COVID-19 pandemic has turned into a global health crisis, evolving at unprecedented speed and scale. The priority of governments and organisations everywhere is to take decisive action to protect their people. The reality is that modern healthcare systems are already under substantial pressure due to demographic changes and long-term affordability constraints. Countries are at different level of capabilities and readiness to deal with a pandemic. Nonetheless, public policy makers and health administrators face a common challenge now: to articulate and execute a health response that mitigates public harm from an entirely new virus. This health crisis needs a rapid and strategic response:

- Strong sensemaking capabilities to enable a rapid and effective response

- The difference in sensemaking and subsequent speed of response underlies the divergent infection curves evident in different countries. Identifying the threat early is the key to preemptive action. Some Asia Pacific nations quickly recognised the cues and rapidly engaged experts to better understand the nature of the virus and inform their testing and containment strategies.

- They acted effectively in the face of significant uncertainty by focusing on making sense of an unfamiliar problem and devising a common map to enable coordinated action, rather than seeking “definitive answers”. Their approach highlights the importance of anticipating rare events and having a plan (even if it is not the perfect plan), that can serve as a springboard to action.

- What is needed instead is a well -coordinated health response. Key to this is recognising the systemic nature of healthcare and the need to coordinate activities across care settings to achieve specific objectives such as broad based containment of virus transmissions.

- Implementing an effective health response strategy during a pandemic also requires focus on intelligent action (which hinges on acquiring and harnessing timely information)

Public alarm tends to increase with the rising infection rates,

but timely dissemination of information from trusted sources

is an effective counterbalance in public health crises

management.Educate the public quickly on facts such as

symptoms and what individuals need to do

differently to reduce the risk of contracting the

disease. To suppress transmission early, consistent

and frequent communications from government

agencies and public health experts are vital. Early and speedy contact tracing and monitoring of

affected individuals is key to containing disease

spread and reducing pressure on public healthcare.

Such aggressive interventions are particularly

important but challenging for nations with large

socio-economically dispersed populations such as

Indonesia, where many of the 270 million population don’t have access to the technology typically used for monitoring.

In many countries, shortages in healthcare capacity such as doctors, medical facilities and testing kits, as well as technology to detect and monitor the disease outbreak continue to prevent an accurate understanding of the pandemic’s trajectory. In South Korea, health authorities have been testing hundreds of thousands of people and tracking potential carriers like detectives, using smartphone and satellite technology. Makeshift testing centres are a critical part of the infrastructure that was created - one hospital in Seoul developed a “walk-thru” test where people sit in a transparent cubicle as a medical worker collects a sample using gloves attached to the front panel – speeding testing and minimising risk to medical staff.

Now we go to Critical Care where public health provide high quality hospital care safely, and at scale to critically ill patients to save lives.

Public health infrastructure can’t expand and modernise

overnight. It requires years of investment in people, systems

and capacity to deliver consistent high-quality care.

When faced with a situation like COVID-19, medical resources

need to be reallocated or repurposed to create surge

capacity for infectious disease or intensive care needs.

Hospital capacity must be balanced between pandemic

demand and other critical illness needs. For an example as in Malaysia, new partnerships between private and public

sectors, or even makeshift facilities, are being

formed to provide surge capacity. For example, the

Association of Private Hospitals of Malaysia

announced in March that private hospitals are ready

to coordinate the management of COVID-19 patient

care in terms of equipment and manpower, so as

not to overwhelm the public healthcare sector.

Lastly we look at the aspect of Recovery and Support where public health focus on recovery and support from the start to mitigate longer term harm.

A truly effective response must extend beyond urgent care to

address the needs and concerns of frontline workers and their

families, as well as the wider community impacted by the pandemic.First responders and frontline carers are inevitably exposed to higher

risk of infection, as well as physical and mental stress. Support must

be provided to avoid such workers being overwhelmed.

Containment measures can lead to social isolation and increased

anxiety. As such, the mental harm of a pandemic can exceed the

clinical harm. Wider community support is required to mitigate this.

Continued monitoring and testing may be required to ensure that

recovered patients remain free of contagion. Given limited

understanding of the pathogen, there remains uncertainty in what

long-term controls are needed to prevent further outbreaks.

WHO and World's Long and Short-term Strategies to Handle Diseases.

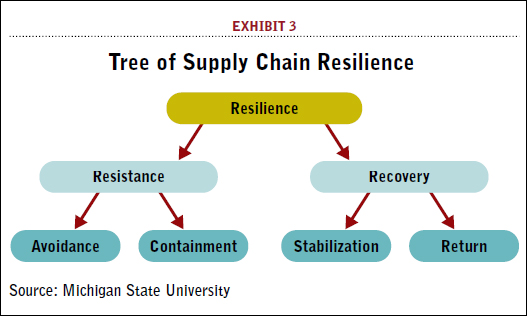

To prepare for future pandemic waves, all organisation ensures that they have good supply chain resilience. They make strategic planning based on pandemic modelling and doing rapid sourcing of critical resources. Intelligent stockpiling and distribution based on medical need.

For the future prevention,a rising mitigation strategy will be used where analytics, social listening algorithms, and fact-checking

platforms to detect rumors that are circulating on social

media and other channels. In addition, once transmission is

detected, contact tracing needs to be activated to identify

the source of infections and the potential clusters in the future.

In triage and treatment, government and organisation will create the right infrastructure for symptom

detection and testing at scale. Fully mobilise crisis management

centre to enable decision makers to model demand across the

care continuum for example home, general practitioners, hospitals, labs,

telemedicine and pharmacies using real-time data. They also can design and invent technology-enabled innovations, such as

AI powered virtual agents, can help alleviate capacity

constraints in telehealth services. Virtualisation of the

primary care network can be extended to expand the reach

to more people, while reducing infection of medical staff.

Sharing how different countries are building

surge capacity will give the global community a better chance

at being ahead of the curve in future crises including

strategies for ensuring sufficiently trained personnel,

protocols, equipment and medication to meet the needs of a

rapidly shifting health crisis. After this pandemic end, public health will re-engage and re-priorities patients whose medical procedures were delayed during the pandemic, in a

compassionate and structured way. Address wider social determinants of poor health in the community. The burden of

severe influenza illness falls unevenly across society. Recognising and addressing the factors underlying this supports both

community recovery in the near-term and increased resilience in the long-term.

Comments

Post a Comment